By Wunna

Dear Mama,

I told you I’m gay in 2014, and I remember the liberation, no matter how fleeting, and I remember likewise, the denial and rejection.

Being disowned is an event that clearly demarcated a new beginning for me. I felt I no longer had a past to return to, and that you remained only a memory. Like opening a mangosteen with the bottom of your palms, or how you read from the couch about different types of rocks from the geology textbook. Igneous, sedimentary, metamorphic rocks. I didn’t know any of those words, but I knew that you loved me back then.

Fast forward a decade, and I am currently reading about love and self-care through black feminist love-politics, and as much as I want to share with you what I’ve learned, I can’t help but ask, why must I crawl my way to theories of love when you existed? Why did you make me choose my own genealogy when I wanted yours?

And why did I have to be disowned for me to start understanding or really listening to what these scholars have been saying?

Self-love as political, self-love as theoretical

As I read about self-love through the Q-Zine entry “Love as Revolution” and through Jennifer Nash’s (2013) “Practicing Love”, I learn that I am part of the world and the community around me and part of loving myself is loving the community around me that nurtures me. Certainly, that is true, but what I hold to be equally true is the reciprocal: that to love my community is also to love myself. And I have been neglecting that, or more specifically, I have been denying this love to myself, and that I’ve been hoping that the love I receive from my community would be enough to nurture me.

I have never said ‘’I love you’’ to myself either. Until now. I love you, Wunna.

When was the last time you’ve told yourself that you’re sorry? Or that you love you?

Through these readings, I realize I have been practicing my own severance, my own disowning. I repeat what I’ve learned and found safety in repetition, comfort in patterns, even if destructive. I’m not selfish for loving myself, and in fact, I have to, even if I am still not fully loving myself on its own intrinsic merit, I still have to, in order to love my community around me.

Part of loving myself is to “transcend myself” as Nash cites the legacy of scholars before her such as June Jordan and Audre Lorde, and to take upon this call, I must find alternative ways of loving myself. In citing Alice Walker’s philosophy of womanism, Nash reminds us that part of the genealogy of black feminism love-politics is the possibility that the unwavering self-love even has the potential to prefigure political and creative projects, because then I can see myself as a safe space to practice different forms of love, and see where I could improve before I can extend healthier modes of connection and compassion to those whom I hold dearly.

Love as Futurity

Part of this love politics is the idea of futurity, and this is especially pertinent to me as someone who has been disowned, because I feel I have been excluded from a future, a continuation of a lineage, and now I have been asked to make my own. I know of “the personal is political”, but as Sara Ahmed says, the personal is also theoretical. From this experience, I can draw upon José Muñoz’s idea of queer futurity, that we must continue to create and enact hope and futurity through art, music, performance, and also through our relationships, especially if we feel that we have been denied a future.

I also want to note the undeniable impact of intersectionality, how we learn of forces of oppression that are mutually constitutive, for example, that racism informs homophobia, and vice versa. This framework has given me a vocabulary to express my multiple pains. Yet as Nash reminds us, drawing on the logics of pain is to focus on the present, and intersectionality as a framework has the risk of petrifying us to the present. For this reason, Nash uses intersectionality as a point of departure and discusses the importance of love-politics and its futurity.

What do you hear when you hear the word feminism? Sara Ahmed provokes us with this question in the chapter Brining Feminist Theory Home. Then I ask the same for you, what do you hear? When you hear words like intersectionality, futurity, interdependence or ethics of care?

Mama, I want to get to know you again. Aside from being my mom, who else are you? Who else do you want to be? Is that couch still there? Come with me, let’s read through these texts together.

With all my love,

Your son, Wunna

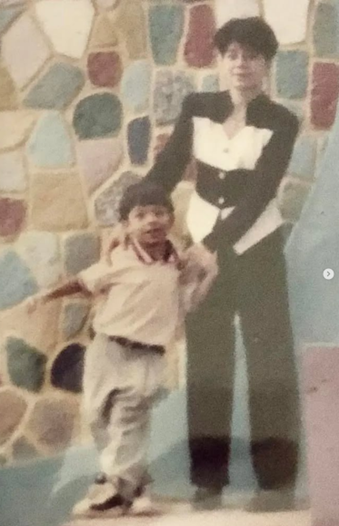

Image caption: This is Wunna with his Mama when he was 5 years old.

Leave a Reply